Big big big—out to the very edges.

We're in outer space, another planet, an alternate reality. Things are not as they're supposed to be, or how they've ever been or will ever be again— and it's the best thing that's ever happened. The boundaries and patterns of nature, the things we take as guaranteed, and the patterns we build in life and the world around us are gone—flipped on their head.

How could I have thought of doing anything else today but this?

We're in outer space, another planet, an alternate reality. Things are not as they're supposed to be, or how they've ever been or will ever be again— and it's the best thing that's ever happened. The boundaries and patterns of nature, the things we take as guaranteed, and the patterns we build in life and the world around us are gone—flipped on their head.

How could I have thought of doing anything else today but this?

I was hesitant to join; it seemed fun but not necessarily noteworthy. But we went out on a limb, and I let Michael rope me into his half-cooked plan to go to Vermont to watch the total solar eclipse. I'd have to take a day off, which is a hassle. But sure, I'll go. It will be a fun road trip with my brother, if nothing else.

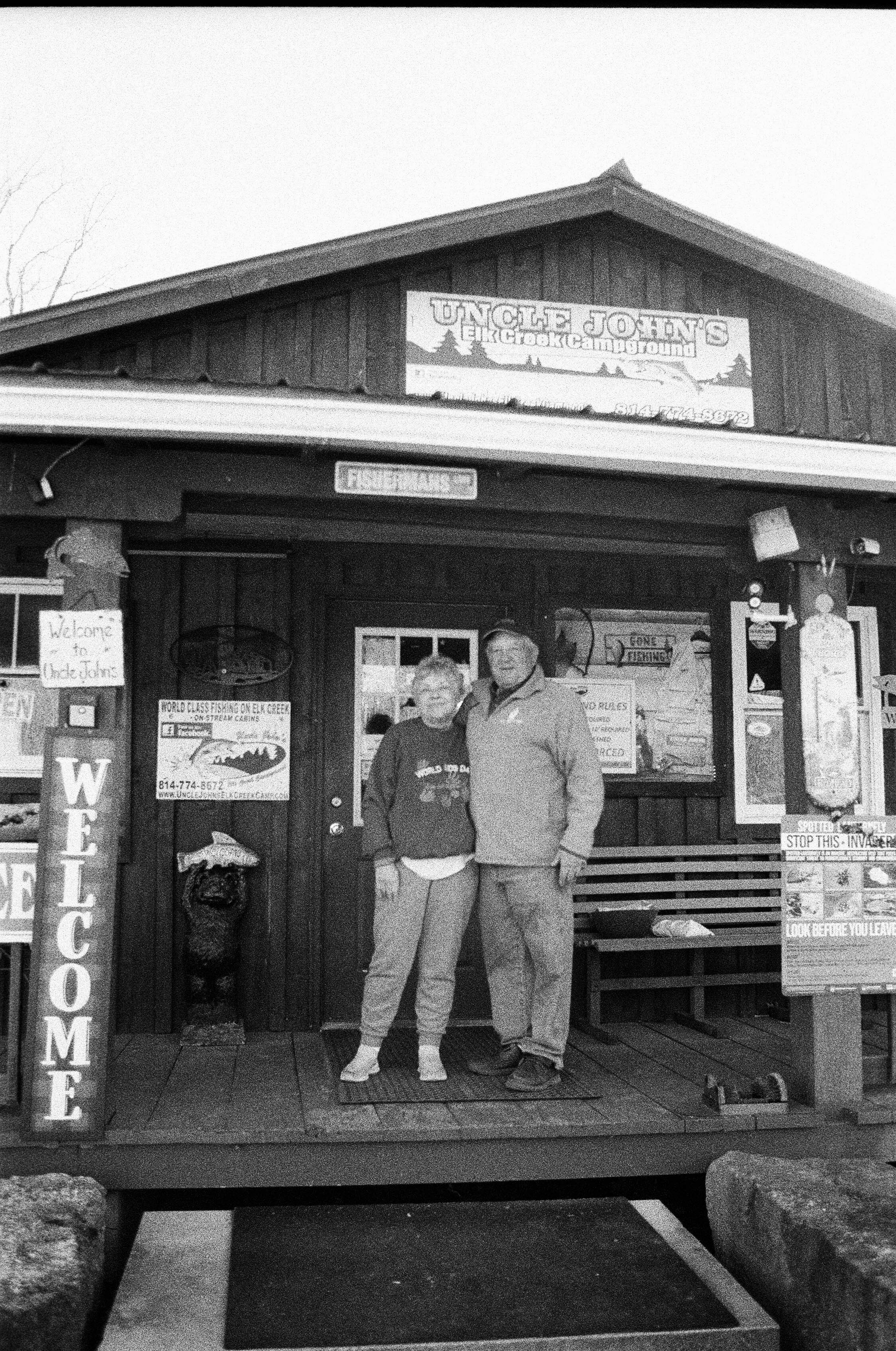

After we decided to go, we found out our little brother, Andrew, and his wife, Katelyn, already made plans to camp overnight in Erie, PA, and watch from there. We pivot and decide to join them. Sunday morning, April 7th, we made the seven-hour drive to Erie. After a miscommunication with the campsite Andrew and Katelyn originally booked, they found a new site at Uncle John's Elk Creek Campground, right in the path of totality.

After we decided to go, we found out our little brother, Andrew, and his wife, Katelyn, already made plans to camp overnight in Erie, PA, and watch from there. We pivot and decide to join them. Sunday morning, April 7th, we made the seven-hour drive to Erie. After a miscommunication with the campsite Andrew and Katelyn originally booked, they found a new site at Uncle John's Elk Creek Campground, right in the path of totality.

We quickly found out that the eponymous John likes to talk. You don't have a conversation with John, and you get caught in an albeit entertaining conversation with John. He pontificates, as his wife describes it. "That's the word of the day," she says, "he goes to McDonald's at 5:30 am and pontificates to his group about the weather and who's died."

"I love my granddaughter." He says, "When I found out my daughter was pregnant with her by a real deadbeat guy, I hired a guy to kill him."

"What happened?" I ask.

"Someone else killed him first."

"That's lucky."

John, according to John, has been in two movies, met Lebron James, his granddaughter is a famous photographer, and her husband is a commander of–

"He's not the commander of anything," his wife interjects.

"John loves people. I don't. I hate people." She says as she kindly chats with us and offers us free iPhone cases from the bowl of iPhone cases in their office, "I got them at The Warehouse."

"What happened?" I ask.

"Someone else killed him first."

"That's lucky."

John, according to John, has been in two movies, met Lebron James, his granddaughter is a famous photographer, and her husband is a commander of–

"He's not the commander of anything," his wife interjects.

"John loves people. I don't. I hate people." She says as she kindly chats with us and offers us free iPhone cases from the bowl of iPhone cases in their office, "I got them at The Warehouse."

The following morning, the relaxation of a fire burning and a coffee in hand was squelched by the impending rain forecast. We quickly packed everything and sat in our cars, watching the drops roll down the windshield, taunting us. Based on the various radars we were monitoring, we decided to drive west, just over the border into Ohio, where the cloud coverage looked more promising.

John pulls up as we're leaving, and before I can say goodbye, he says,

"Take down this number."

I take it down.

"That's my granddaughter's number. You should hang out with her."

"Where does she live again?"

"Alabama."

"Okay, John."

"Take down this number."

I take it down.

"That's my granddaughter's number. You should hang out with her."

"Where does she live again?"

"Alabama."

"Okay, John."

We arrive in a small town, Conneaut, just west of the Ohio border. It feels like a cross between a suburban, midwestern town and a shore town. We pull into a park with an open field and a steep set of stairs leading to the shore of Lake Erie. Thick, mashed potato clouds loom as far as we can see as we debate whether we should go farther west. We decide to stay and take our chances. It's early, 10 am, and I don't expect the clouds to clear. Or at least I'm not letting myself believe it.

We spend the next few hours kicking around, watching the sky, and holding out hope.

We spend the next few hours kicking around, watching the sky, and holding out hope.

The anticipation heightened as the clouds began to break and little bits of blue sky peaked through. The parking lot filled up, and the beach drew swarms of people. Andrew had an eclipse timer that counted down to the total eclipse. First contact is when the moon first "touches" the sun. Second contact is the total eclipse, and the third contact is when the moon moves past the sun.

We set up chairs and a telescope, and Michael set up his camera in the field in preparation.

![]()

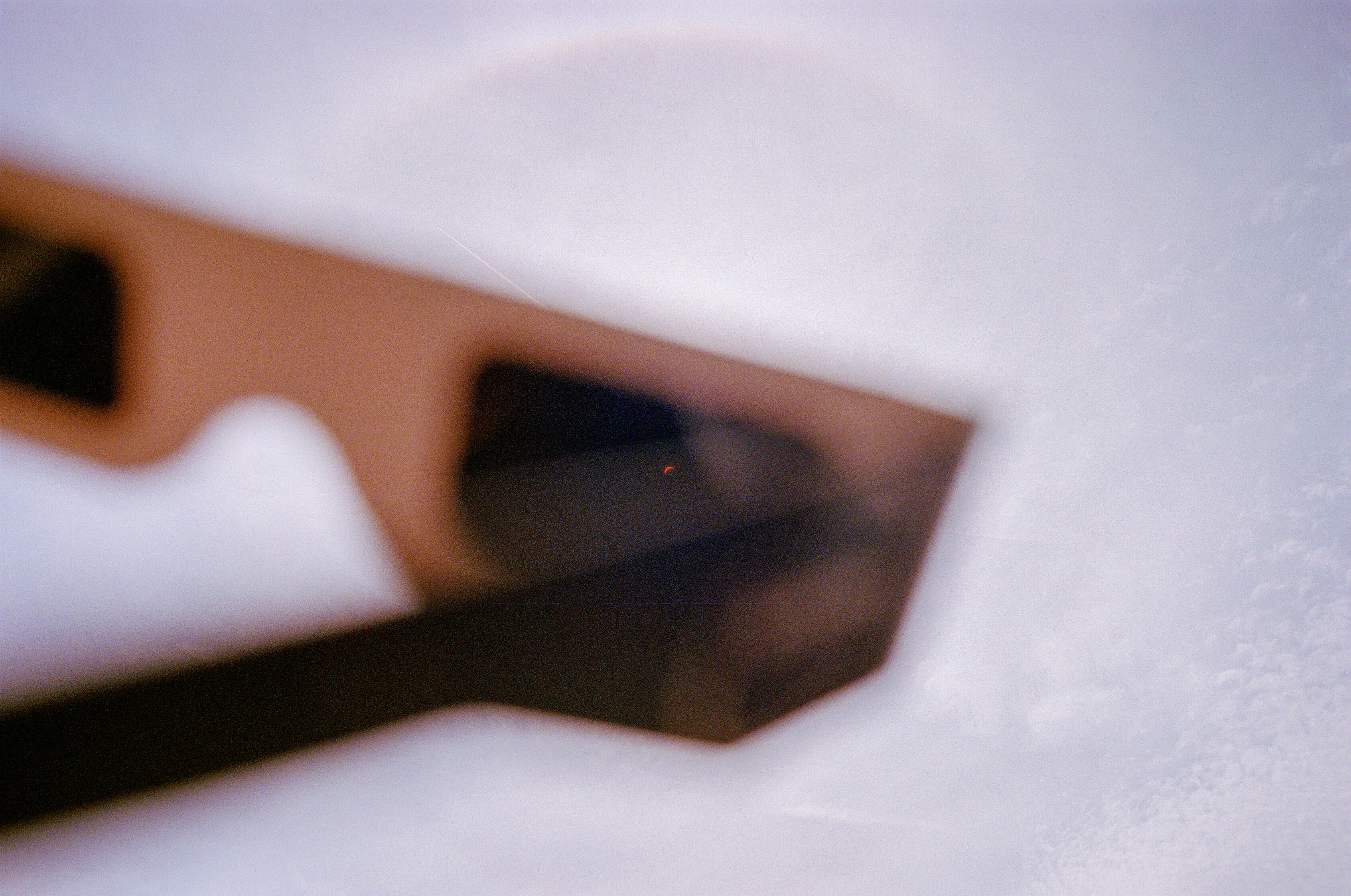

The clouds have cleared; just wisps remain. "First contact," the voice of the timer app announces. We gaze towards the sun with the protection of eclipse glasses. The slightest dent appears in the sun as the partial eclipse begins.

I wander the beach. We'd have roughly an hour before second contact. We are filled with nervous excitement as realize we might actually see it, without knowing yet what "it" really is.

We set up chairs and a telescope, and Michael set up his camera in the field in preparation.

The clouds have cleared; just wisps remain. "First contact," the voice of the timer app announces. We gaze towards the sun with the protection of eclipse glasses. The slightest dent appears in the sun as the partial eclipse begins.

I wander the beach. We'd have roughly an hour before second contact. We are filled with nervous excitement as realize we might actually see it, without knowing yet what "it" really is.

"5 minutes to second contact."

I'm staring at the sun, at the moon; even 99% covered, you cannot look at the sun without eclipse glasses. Your body knows, and your instinct knows not to look up.

“30 seconds to second contact”

Pure unadulterated unhindered no barrier.

I can see a sun flare. I can see it. I can see it. Here, with my feet on Earth, my bare eyes can see a detail of the sun. In a moment, we were transported to an alternate reality.

The temperature dropped 20 degrees in a few minutes, and a 360 sunset surrounded us. The light was different—muddier and odd. The same world, the same nature, but a totally different version.

There is an overlap between this experience and being in immense, untouched nature—a similar, humbling feeling. Staring at the moon framed by the sun's glow, I may as well have been transported there, looking back at the world and being washed over with relief at how small and finite we are and reminded how much we needlessly complicate life.

Still, being alone in a vast natural setting and being there with others, even just one other person, are two different experiences.

Being alone, I can sense my eternal self sync its frequency with nature and am apart from myself and one with something eternal. Out of body, as they say. When others are near, it is more difficult to see past my anchorage to the now and the physical.

Even alone in nature, the sweetness of the experience is always slightly soured, knowing that it's not safe. Every moment is tainted with sadness, knowing that the wrong person with the right amount of money could level it—nothing is totally out of reach from our avaricious grasp.

I know the moon is within our reach, but it feels safer. The distance—the illusion that space is beyond us—purified the experience. It was beyond us.

Experiencing this phenomenon was made exponentially more whole and joyful by sharing it with strangers. If I had run up to the closest person and hugged them in the middle of it, they would have just hugged me back. It's the kind of thing that should end wars. End them before they start. And make us quit our jobs, plant a tree, and watch it grow for hours, days, weeks on end, and rise feeling that we had the most productive time. Or that it would eradicate the concepts of productivity from our understanding of life.

"30 seconds to third contact" Trying and failing to soak up the whole thing. "10 seconds to third contact." "Glasses on! Glasses on!" "Third contact." In an instant, the sun shone bright and burning, and the world morphed back into itself.

Here, in a tiny town in Eastern Ohio, we were teleported into another world. Then, we were quickly shuttled back into regular life, and the pattern we participated in whisked us away from that brief, glowing moment of weightlessness—of unhindered being and joy and awe and gratitude and sheer delight. For a few minutes, without moving, we were transported elsewhere. Suspended somewhere between Earth and the galaxy, between expected and alien, swimming through a magical place, totally new yet entirely familiar.

As with everything, life moves on, and the memory fades, but the impression is left. A notch in our tree rings, a nudge in our trajectory. We continue in the same life but in a slightly new direction, with a new knowing, humility, wonder, and warmth.